The text here is a condensed version of my thesis defense text:

Three years ago I stood at the podium in the classroom at VSW to give a presentation on my art practice as I prepared to begin working on my thesis. I remember clearing my throat and saying “hi, my name is Nilson,” at which the room burst out into laughter. I think about this scene often.

I’m a ROM hacker, a glitch artist, a barista-poet, a filmmaker, an intern, and an organizer. I make weird video games, anti-video games, and queer video games that draw heavily from my autobiography, my relationship to my body, and my understanding of genre and medium. My preferences are non-salable art, flashing lights, difficult puzzles, spatial poetry, and magic spells.

I grew up mostly concerned with Japanese Game Boy games and drawing dream maps, and I grew up with an estranged older brother who gave me his old Sega and tons of shit for liking anime and who himself grew up to be the leader of all the punks in Rochester. As a kid I played video games no one else had ever heard of, games with names like “The 7th Saga” and “The Secret of Evermore,” games without guns for sensitive kids with no friends.

My family never went to church, so Saturday morning shonen anime was my mass, repeated play throughs of The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy my parables, stories of lost children working together, combining their bodies and spirits in the face of fascism and intolerance.

No one in my family would talk about sex, so I learned all about it from cable TV, and later, I learned about intimacy while lurking in DeviantArt chatrooms. From an early age, I had a negative relationship with my own body, how it looked and how it felt to be inside it.

When I was 12, I fell in love with the bassist of a band they played on MTV, and I shopped at Hot Topic and bought grindcore t-shirts. It sounds dumb but it was amazing and drove my dad crazy. I made a game in RPG Tsukuru Super Dante where you play as that bassist and have to recover the tightest jeans in existence from an ancient tomb. It was the first video game I ever made, and maybe the most radical.

As a teenager, I became an acolyte of dada mysticism, printed out pictures of Tristan Tzara and Arthur Rimbaud and pasted them with hearts on my trapper keeper. Dada poetry was perfect, swift and not unlike the poetry I was reading in video games, complete with glitches, illusory walls, and incantations.

With the power of the internet, I downloaded all the games from Japan I had read and dreamed about, and I learned about ROM hacks, and I discovered Dragon Pervert, the first major Bad hack, which changed my life.

In part, my art practice is a ritual to deal with being eternally stuck between the brutal toxic queerness of the Marquis de Sade and the radical softness of Build-A-Bear, to question what those extreme poles mean in relation to each other, and to begin to untie the knot on my own manic depression, physical pain, and inability to form a positive relationship with my body.

I ask myself, has this process been therapeutic?

There is a sensibility running through queer theory related to queer pleasure, a non-heteronormative or non-mainstream pleasure, pleasure unlinked from the fissures of reproductive futurism. Pleasure here is a potential, a path toward an as of yet unknown utopia.

Pleasure is also an intrinsic assumption tied to games and play. I see a problem with the medium when video games are only expected to give pleasure, only expected to raise our serotonin, to give us an escape.

With this thesis, queer pleasure, of which I know little of, and the pleasure associated with play, a feeling close to my core, are both subverted and forgone.

Perhaps there is a queer utopia of pleasure, but I do not yet know it.

My art practice has become my relationship to making, playing, and seeing. This relationship is one of the most important relationships in my life, and often is the only way I can share my experiences, feel value in myself, and untangle the secrets I keep.

I’m interested in the abstracted body here, the body designed to be put through violence and then transfiguration, the mistranslated body, the mutable body, the living then dead body.

You’ll hear me speak about Dragon Quest, or Dragon Warrior in the US, at length. Released in 1986 in Japan, Dragon Quest is the template for all role-playing games, half Dungeons and Dragons and half Dragon Ball Z, a young person’s religion, and the genesis of many video game assumptions. It is the original myth and math.

My relationship with Dragon Quest begins when I am nine and in a doctor’s waiting room. I’m playing Dragon Quest II on my Game Boy. The image is this: my two friends are dead and I carry behind me their corpses in coffins to the only nearby cathedral. Inside, the priest will revive them with God’s grace, but it will cost me more gold than I have. I sell all my clothes, and my dead friends’ clothes, too, all our drugs and charms, and it’s still not enough.

The “Bodies are a problem” projects would manifest as poems, anti-video games, and other difficult pieces [see: the Cathedral of Shit], each an attempt to make sense of my own problematic body, the binaries that bind all of our bodies, and the violent gnostic hellquest of games that very much recalls the violent gnostic hellquest of real life.

To share my experiences of bloody, scarred bodies, unsolved, psychosomatic health problems, and the stranglehold of a binary-leaning, socially constructed understanding of sex and gender, I dug hard into the assumptions of video games, the laws and systems over the bodies I knew best, these digital ones.

Violence is intrinsic to even some of the most abstract video games. Competition is intrinsic in almost all games. Play philosopher Roger Callois refers to competition back to the Greek value agon, which conjures what else but our word agony. Most video games are designed as exchanges of violence between player and game, agonizing and antagonizing algorithms.

I think of the time I’m at a new year’s eve party, and I’m playing Dark Souls in the living room, while a few people watch. I plunge my sword into bodies representing pure violence, killing and gaining power. Even though no one seems to mind, I apologize every time I murder a giant animal. In private, I don’t hesitate, but this masculine-coded performance embarrasses me in front of an audience.

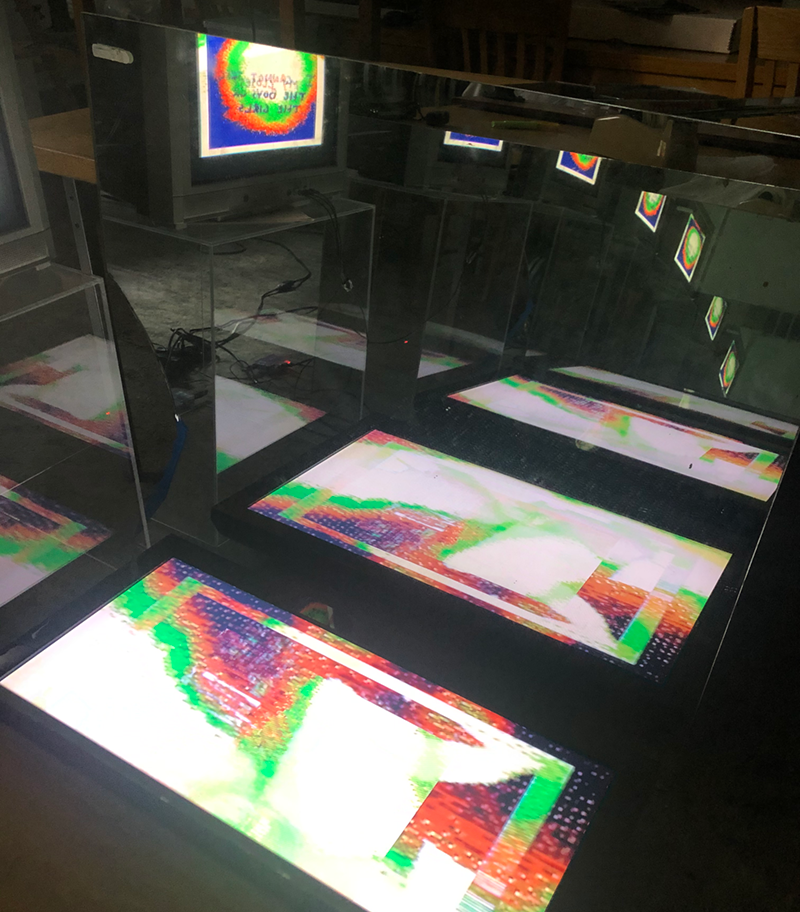

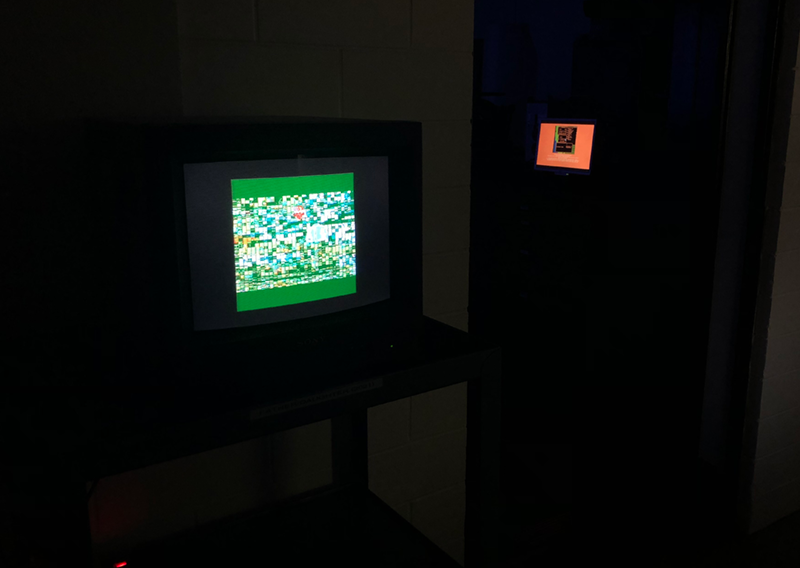

My practice involving glitches lessens the distance between my body and what is beyond the screen. The corruption process, both heavily mathematical and totally randomized, is a craft process, hand-driven, a performance, an ecstatic puzzle solution. Equations form an imperfect math, a digital numerology, breaking the code in truly random but also predictable ways. What remains of the original game is an appropriation, a shattered picture frame, the border of a dead lottery ticket.

A stop and start staccato rhythm is captured as the real-time glitches transcribe a new meaning to the intro sequences of these game quests. The pleasure of games is disrupted, and a difficult, technical poetry emerges. Like an exquisite corpse, hex values are inverted, and point to other hex values, which get inverted, too. Repetition is inevitable but important, waiting for a climax that never comes.

I understand that the language and signs of a thirty year old Japanese role-playing game are esoteric. I know that I alone feel the ecstasy of stumbling upon a new double-tile sprite on the world map beside a white coastline at dusk.

All I can do is point to these moments, and maybe someone will believe me.

Touch is vital to the games I make, and with the ongoing pandemic, it has been a difficult untangling to decide how to show the work. Often, sitting around together is the best way to experience it, but this recently has been an opportunity lost to us, or at least one re-colored with death, sickness, and irresponsibility.

Each piece can lead into the next, as most of the work is a reaction, a denial or an explanation of a previous work. They build on each other, their metaphors and poetries, and subvert them, too, like additive and subtractive color spaces. This is a dungeon, a haunted house, a 3D video game environment. We move in and out of infernal classrooms, the hell version of the familiar. Sequences are spaces, and spaces are poetry, and poetry is magic. Have I said this before?

The thesis exhibition is a collection of related works made between 2016 and 2021.

This collection of work was exhibited at Visual Studies Workshop (Rochester, New York) in May 2021.

nilson carroll