Commodification of (Queer) Love/Intimacy

in Dating Sim Game Mechanics

This text is from a talk I hopefully give/gave for Narrascope 2020. Due to COVID 19, I was unable to attend Narrascope, and the talks were streamed online instead.

My name is Nilson Carroll. I’m an MFA thesis candidate at Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester New York, where I’ve been studying film, new media, and performance art, with a concentration in making and writing about queer games and game experiences.

Video games deal with exchanges between player, game, and game maker. Often these exchanges are aestheticized with violence, but sometimes not. Dating sims are unique in that their exchanges are concerned with love, romance, and sex involving the player, the player character, the game’s characters, and the game’s systems.

For most video games, including dating sims, the virtual body is a site in which points are scored, a notion parallel to the continuing neoliberal narrative of earned progress through bodily labor. Dating sims are of particular interest to me as they commodify the seemingly non commodifiable, love and intimacy between partners.

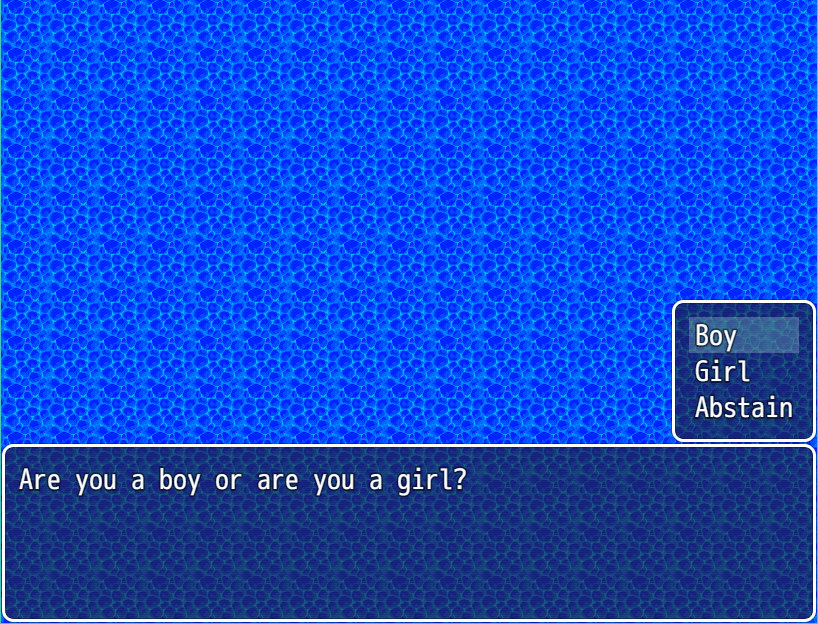

Tim Rogers, in his winding epigram “can video games be our friends?,” describes the usual dating sim set up: Your character is a teenage boy, a nearly blank slate. You are a student at a high school. [...] Your character has four statistical attributes you are free to grind at your leisure. They are "fitness", "smarts", "sense", and "charm". You grind these by carefully choosing your activities every day. You can only choose four activities a day. [...] Each girl has different criteria for her future boyfriend. The tennis girl would like a guy to be physically fit. Of course. The library girl would like a guy to be smart... etcetera.

The basic premise of the dating sim is to optimize your game time, decode the binary stereotypes presented and enact them to earn the trophy the player likes best. Dating sims opt for a black and white series of clicks and choices in order to earn progress toward an obvious, gameified romance.

For instance, the player can buy the “seductive” love interest who always wears red a bouquet of red roses, earning valuable intimacy progress. By following through with this gameplay loop, the player is transformed into a sort of laborer caught in a system where calculated, perfect work replaces real, messy intimacy. The goal is clear from the beginning: the love interest is designed to fall in love with the player or playable character. The typical variation of love interests acts as a kind of consumer market, designed to appeal to audiences.

Most dating sims work to reinforce the role of the player as a love-laborer. Ryan Koons’ HuniePop, an adult dating sim that features a tile-matching mechanic feels like an archetypal representation of the genre. Players are given a choice to play as a male or female character and then pursue around a dozen women of varying anime stereotypes. While players get to choose their gender, this is merely a cosmetic choice. As the player gets to know each girl by selecting them from an itemized inventory screen, feeding them and showering them with themed gifts, they earn hunie, an in-game love currency to spend on traits that make the playable character more dateable.

In-game days pass and players level up and eventually max out the intimacy meters of every woman by doing well at the tile-matching game. After scoring enough points with a love interest, the tile-matching game no longer represents a date but a sex scene that the player has earned, with every tile match granting pleasure in the form of points.

It is here that the body is most represented as a site at which to score points, as the in-game currency numbers caress the character’s body.

Other dating sims operate similarly, but also are interested in subverting certain expectations.

2017’s Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator is explicitly queer in its representation, featuring a whole neighborhood of dateable queer dads of varying personalities. While its gameplay loop feels similar to HuniePop’s, allowing players to choose dads from its social media styled date menu, there are a few key differences. Dates are graded based on answers given, but the dads’ bodies are never turned into trophies - each dad has agency in his world, and even the lustiest dads’ lives don’t revolve around the player. Word choice is important in language heavy dating sims - here, the word “friend” is often used, focusing on a friendship that could possibly lead to intimacy. Relationships are ambiguous, and even a player who earns good grades could possibly not end up with his eponymous dream dad.

The dads in Dream Daddy are difficult to categorize, and stand apart based on their relationship preferences more than anything. There’s a one night stand dad, a dad trying to raise a religious family, and everything in between. Correct answers and scoring points are here mostly as satire and are not in the forefront. Dream Daddy is more interested in telling cute stories and dad jokes than rewarding proper play with sexual trophies.

Beautiful Glitch’s Monster Prom features a diverse cast of monsters to woo and possibly take to the high school prom. Players can assign themselves their own pronouns and date any of the available characters, but what is most striking about a playthrough of this game is the ambiguous nature of its systems: characters of different species meander around the school with their own ambitions and stories. Yes, the world of Monster Prom is highly gamified, but it forgoes many of the inherent binaries that structure most dating sims and opts for a highly fluid dating experience where seemingly anything can happen and sex is never owed.

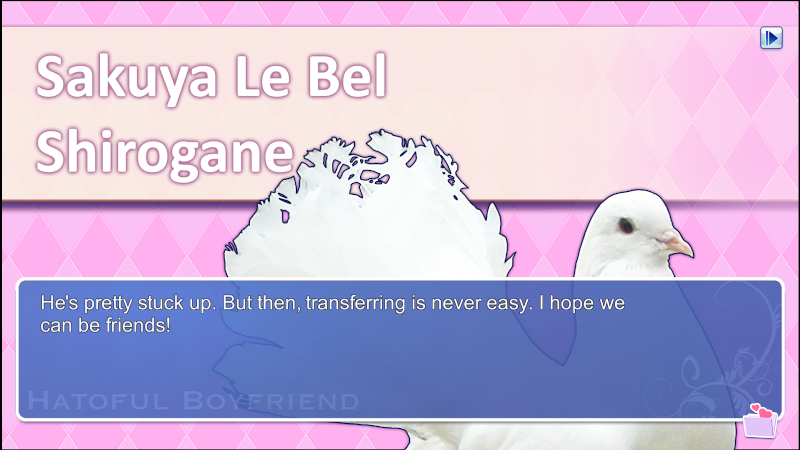

As the queer indie game boom continues, there have been a handful of dating sims that subvert the assumed male gaze of the player. Hatoful Boyfriend forgoes the presence of human bodies altogether, instead asking the player to date pigeons. Here we go through the motions of the dating sim systems, but without the explicit goal of male-gaze oriented human eroticism. Doki Doki Literature Club! subverts the dating sim formula by disrupting the final part of the equation through its fourth wall breaking metanarrative. The wonderfully queer I Love You, Colonel Sanders! parodies the genre with ridiculous branding and absurdist humor.

What these three games have in common is their status as parodies that closely mirror the rhythm of the genre they’re parodying. Players choose love interests and answer binary calls to further attraction statistics. These games aren’t trying to function so much as realistic narratives about intimacy, instead operating as novelty, experiment, and comedy, respectively.

While not a dating sim in the visual novel sense, I would cite Jimmy Andrews and Loren Schmidt’s Realistic Kissing Simulator as a queer intervention of dating and intimacy in games. After giving consent, two players control two tongues with no set or given goals.

In Video Games Have Always Been Queer, Bonnie Ruberg writes that “almost all standard in-game structures by which progress could be determined have been stripped from the game.”

The suggestion that kissing should have no goals is especially powerful here in the face of the dating sim genre, which keeps close track of intimacy statistics and progresses. Realistic Kissing Simulator simulates kissing while explicitly abandoning gaming’s obsession with feedback/compulsion loops, accomplishments and quantifiable outcomes.

Another queer indie game I would cite is Anna Anthropy, Leon Arnott, and Liz Ryerson’s Triad, an intimate puzzle game that uses the bodies of three lovers as puzzle pieces. Anthropy describes the game as being “about the most difficult puzzle of all: human relationships. The goal of TRIAD is to fit three lovers in a bed in such a way that everyone can get to sleep comfortably.” Absent are numerical statistics for each lover. Players do not control one lover over the others and if one lover isn’t happy, none of them are. The puzzle is a genuine attempt toward love. Yes, it has a goal, but this goal is nameless and selfless. Any eroticism is implied and ambiguous, abstracted.

So, why does this matter and what can dating sims learn from these examples?

Human relationships are not binary experiences with explicit goals. The person you’re on a date with doesn’t have to change their behavior based on your stats or the color of your gifts. I argue for a re-thinking of the dating sim genre and its systems of commodification as well as the real-world implications of those systems reflected in social media, dating apps, and general socially constructed hierarchies.

What opportunities and expressions arise when the goal of increasing structured intimacy is removed from dating sims? What does a hanging out sim look like, or a friend sim, or a stranger or a sibling sim? How do relationships function when sex is not the ultimate goal, or in the case of most dating sims, the end of the game?

I would challenge game designers to, again, in Ruberg’s words, allow players to play queerly, to play in a “mode of nearly infinite possibility, brought to games largely through their players rather than the systems structured by (mainstream) developers.” Or in Heather Flowers’ words, from their Meatpunk Manifesto: make all your art as gay and trans and leftist and intersectional as humanly fucking possible.

May 2020

~ nilson carroll

References:

Flowers, Heather. "Meatpunk Manifesto." 2018. https://hthr.itch.io/meatpunk-manifesto

Rogers, Tim. "can video games be our friends?" Kotaku, November 2, 2009. https://kotaku.com/can-videogames-be-our-friends-5395084

Ruberg, Bonnie. 2018. Video Games Have Always Been Queer. New York: NYU Press.